Once you have crossed the threshold of the portal, you come into the area that leads into the monastery. The area as we see it today is the result of alterations done in the mid-18th century. Prior to the community’s expulsion from the monastery, this area was given over to services outside the monastic life, such as the stables and workshops, as well as the homes of the lay population that served the monastery. These services included the smithy, which occupied one of the buildings adjoining the gate.

The Gate of the Assumption, presided over by an image of Our Lady and the coat of arms of Santes Creus, linked the outer complex with the semi-cloistered area, a restricted space to preserve the monks’ isolation.

The Gate of the Assumption leads into the semi-cloistered area, currently called the Plaça de Sant Bernat Calbó. The customs of the Cistercian order called for this transitional space between the cloister and the world outside so that the monastery could fulfil its duties of hospitality and deal with the financial activities in which it was involved with no interference in the life of the community.

In the 16th century, Abbot Jeroni Contijoc (1560-93) moved his residence from the rear cloister to Plaça de Sant Bernat. The new palace used part of the structure of the former Hospital of Sant Pere i Sant Pau for the poor, built in the 13th century thanks to a bequest from Ramon Alemany de Cervelló for the construction and upkeep of a hospital that would take in pilgrims and give alms to the poor.

According to the ideal concept of a Cistercian monastery, the rooms and outbuildings occupied by lay brothers were to have been built in this now empty space. Monks and lay brothers alike lived in the monastery, the difference between them being whether they had made a monastic profession. This difference, often determined by social origin and educational level, was particularly marked in monastic life. Monks and lay brothers took on very different tasks and even occupied separate spaces within the monastery. The monks devoted themselves mainly to study, whereas the lay brothers did the manual labour. Lay brothers were exempt from complying with all the religious duties to ensure that they could devote themselves to farm work, crafts and the maintenance required for the upkeep of the community.

The monastery did not have defensive walls properly speaking but was fortified by raising the height of the walls of the cloistered complex and reinforcing them with battlements. In order to protect the defenders, the gap between the battlements was covered with folding pieces of wood.

The Royal Door was the main entrance to the enclosed monastery. It was built as part of the works to construct the Gothic cloister in the 15th century and was sponsored by James II and Blanche of Anjou, as indicated by the royal effigies and coats of arms sculpted in the arch over the door.

The cloister is one of the most significant features of Santes Creus, not just because of its artistic quality but also because it was the first Gothic cloister built in the kingdom of the Crown of Aragon.

A small edifice extends off to the side of the south gallery of the cloister. This houses the basin where monks washed their hands before entering the refectory. According to the ideal plan of Cistercian monasteries, the lavatorium would be situated in front of the refectory.

In front of the lavatorium is a door that, in accordance with the guidelines for Cistercian architecture, must have led to the old refectory. Alongside it, there would have been the kitchen and the cellar, which has also disappeared. Even though nothing of the refectory has survived, documentation reveals that Queen Blanche of Anjou provided a legacy in her will for it to be constructed.

One of the daily rituals of monastic life took place in the chapter house, the reading of a chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict. The chapter house is one of the most significant rooms in a monastery due to the importance of its function, and in the case of Santes Creus, it is one of the most outstanding rooms at an architectural level. This space is part of the first section to be constructed, dating from the 12th century, and is notable for its austerity, simplicity and balance.

The chapel occupies the space of the monastery’s former armarium, where the books used in the chapter and during reading sessions in the cloister were kept. In 1558, it was converted into the funerary chapel of Magdalena Valls de Salbà, the sister of Abbot Jaume Valls. The works were paid for by a bequest that Magdalena herself left in her will.

Work began on the construction of Santes Creus church in 1174. Even though the works continued until the early 14th century, it opened for worship in 1211. The church, dedicated to Mary, Mother of God, as is the custom in the Cistercian order, was for the private use of the community. It was not until the seizure of Church property that it took on the role of the parish church, which the Church of Santa Llúcia had previously been.

The parlour connects the main cloister and the rear cloister. It was a thoroughfare but also a meeting place, as demonstrated by the stone benches up against the wall that were formerly lined with wood to make them more comfortable. The monks were able to hold brief conversations here, though always prudently, since the Cistercians lived in silence as they believed in its spiritual benefits.

Santes Creus has a second and more artistically simple cloister that structures the outbuildings situated at the rear. It was built in the second half of the 14th century, during the time of Abbot Guillem Ferrera, in order to provide some order to this area and to connect the abbot’s palace with the rest of the monastery.

One of the tasks undertaken by medieval monasteries was to copy manuscripts and to draft documents. Cistercian monks also engaged in this work but St. Benedict laid down restrictive rules to preserve the order’s austerity by reducing the range of colours, limiting ornamentation to capital letters and eliminating figurative elements. Even so, the order also produced lavishly illuminated manuscripts when these precepts were relaxed.

A small door leads into the prison cell, a cramped and damp space used as punishment and penitence cell by the brothers. The abbot needed to know the most appropriate way to correct the behaviour of his monks and would even consider the possibility of physical punishment. In the most extreme cases, he might even contemplate a prison sentence.

The construction of a new refectory meant that the kitchen had to be moved so that it was next to the monks’ dining room. Most of the roof over the room has disappeared and there are few elements that make it possible to determine its original function. The surviving remains include the water conduits and the basins, a table and a stone hearth where pots were placed over the heat. There is also a hand mill and the remains of millstones from a flourmill.

The refectory of the rear cloister appears in documents dating from the 16th century, though its appearance today is due to works done in 1733 to allow more natural light to enter by raising the ceiling and opening up two additional windows, one at each end, above the cloister galleries.

The palace was the abbot’s residence and the centre of the administration of the monastery. The functions of the abbot of Santes Creus were not confined to the spiritual guidance and governance of the monastic community, as he also had duties as a feudal lord and a Church representative of the Corts (Catalan Parliament). In addition, for a very long time he enjoyed a close relationship with the Crown thanks to the fact that the abbots of Santes Creus also held the title of Royal High Chaplain. By virtue of his position and authority, the abbot was obliged to maintain constant contact with the outside world, justifying his need for a residence of his own, through which he was also able to express the power of the monastery.

Once the Cistercians had decided to settle in these lands on the bank of the Gaià River, the community from Valldaura would have erected these temporary buildings for use while the basic rooms of the monastery were being constructed. These building were later remodelled and remained in use till the monks were expelled. It is known that there were buildings with coffered ceilings made of wood and plaster in the 16th century.

Situated in the rear part of the monastery complex, the Chapel of the Holy Trinity was undoubtedly the community’s first church from the time it moved into Santes Creus in the 12th century to the opening of the main church for worship in 1211. Subsequently, when new outbuildings were constructed in the rear cloister, it was turned into the infirmary’s chapel.

Retired monks who had been in the community for more than 40 years and elderly monks lived in especially adapted homes built in front of the palace, on the opposite side of the cloister. Very little evidence remains of this construction, though an impressive long and very flattened Catalan or segmental arch has survived, despite the destruction caused during the Third Carlist War (1872-1876).

The origins of this building go back to the refurbishment work begun on the monastery in the 17th century in order to reorganise the community’s living space. This new construction would have housed stores for clothing and washing-places on the ground floor, while the upper floor was given over to the infirmary.

In 1575, Abbot Jeroni Contijoc ordered the construction of the Tower of the Hours for the bells that are operated by the church clock machinery and which ring to mark the rhythm of monastic life.

The cemetery is indicated by a single stone cross, as the Cistercians did not permit elements that would distinguish between the members of the community.

The dormitory was included in the first phase of construction. Work on it began in 1191 and was completed in 1225, though some historians suggest that the construction could have continued in a second phase that ended in the second half of the 13th century.

Once you have crossed the threshold of the portal, you come into the area that leads into the monastery. The area as we see it today is the result of alterations done in the mid-18th century. Prior to the community’s expulsion from the monastery, this area was given over to services outside the monastic life, such as the stables and workshops, as well as the homes of the lay population that served the monastery. These services included the smithy, which occupied one of the buildings adjoining the gate.

The smithy, like the mill and the oven, were monopolies held by the monastery. Within his domains, only the feudal lord was entitled to provide these services, which he rented out.

You enter the monastic complex via a door set between the houses originally used as the porter’s lodge and the smithy. Above the entrance arch is the Santes Creus coat of arms.

An engraving on the façade indicates it was built in 1475 as part of the reform work undertaken in the complex.

Santa Llúcia was the parish church used by the residents of Aiguamúrcia and Les Pobles, labourers who worked the lands of the monastery, to whom they were bound as vassals.

The current building dates from the mid-18th century, though religious services at the site are documented since 1192.

As in other places, in the 14th century the abbot gave the Santa Llúcia parishioners neules (a traditional rolled biscuit), spiced wine and broth during the Christmas festivities. Evidence of this custom is provided by a neules mould bearing the coat of arms of Abbot Porta, held in the Vic Episcopal Museum.

The Gate of the Assumption, presided over by an image of Our Lady and the coat of arms of Santes Creus, linked the outer complex with the semi-cloistered area, a restricted space to preserve the monks’ isolation.

This was remodelled in the 18th century as part of an overall refurbishment project for the monastery. For this reason, decorative elements typical of the Baroque predominate.

The building contains the home of the vicar, the monk who officiated the religious services in the Church of Santa Llúcia, attended by the people living on the lands owned by Santes Creus. The tower at the top could have served as a conjuratory, a small edifice used on the Feast of the Cross (3 May) for holding a ceremony to bless the lands of the domain to ward off storms and other poor weather conditions.

The Gate of the Assumption leads into the semi-cloistered area, currently called the Plaça de Sant Bernat Calbó. The customs of the Cistercian order called for this transitional space between the cloister and the world outside so that the monastery could fulfil its duties of hospitality and deal with the financial activities in which it was involved with no interference in the life of the community.

The buildings around the space were refurbished between the 16th and 17th centuries to provide accommodation for retired monks and the new residence of the abbot. Lodgings for visitors and the administrative buildings were located here, as were the homes of the monks, such as the apothecary or those in charge of the mills, who were released from their cloistered lives because their tasks required them to have regular contact with the outside world.

Standing in the middle of the complex is the fountain dedicated to St. Bernard Calbó (1180-1243), who was the abbot of Santes Creus and the bishop of Vic. This sculptural work dates from the mid-18th century, shortly after Bernard Calbó was canonised by the Church (1710). St. Bernard was one of the most influential abbots of Santes Creus in both the political and the religious sphere. His opinion influenced many nobles to join James I on his quest to conquer Mallorca. Months earlier, they met at the monastery so that they could put their wills in order, declaring their wish to be buried there and granting numerous properties that significantly increased the monastery’s possessions. At the religious level, he also provided guidance for the reform of religious discipline.

The row of houses on the left of the square was set aside for monks who had retired or whose tasks required them to have contact with the outside world. In the beginning, the customs of the Cistercian order allowed these monks to live outside the monastery walls only as an exception to ensure they did not disturb the life of the community. However, as a result of the relaxation of monastic discipline, only novices remained cloistered, while the monastery’s superiors went and lived in nearby houses and had servants. The cost was covered by the income they each earned in the exercise of their tasks.

All these buildings have been remodelled on various occasions to adapt them to more appropriate uses. The dates shown on the façades (1560, 1645 and 1652) are testimony of this refurbishment work. The ground floor was used as a store, while the home proper was situated above. In order to give these buildings a sense of unity, the façades were covered during the Baroque period with sgraffiti representing columns, cornices and various decorative motifs.

These homes provided the basis for the formation of the village of Santes Creus in the 19th century. Following the seizure of Church property, the houses were distributed among the new owners, who adapted them to convert them into summer homes. At the same time, tenant farmers were encouraged to move into the houses in the first complex to ensure the newly-acquired land was still worked.

The square forms a passage that leads to the monastery church, situated at the highest point. The church façade is divided into three volumes: the tallest central volume corresponds to the nave and the two lower ones to the side correspond to the lateral aisles. It is possible to identify three different periods of construction in this façade. The large gate, the two windows with round arch and the two reinforcing buttresses at the ends are evidence of work in the Romanesque style. The large Gothic window of the central nave decorated with impressive stained glass is the result of a second phase of construction in the 13th century. And lastly, the merlons, built on the orders of Peter the Ceremonious and completed in 1378, are evidence of a third historic moment.

In the 16th century, Abbot Jeroni Contijoc (1560-93) moved his residence from the rear cloister to Plaça de Sant Bernat. The new palace used part of the structure of the former Hospital of Sant Pere i Sant Pau for the poor, built in the 13th century thanks to a bequest from Ramon Alemany de Cervelló for the construction and upkeep of a hospital that would take in pilgrims and give alms to the poor.

The most notable feature is a small Renaissance cloister that dates from before the construction of the palace. The rooms are distributed on two floors linked by an 18th-century staircase, and they overlook the garden through a double gallery.

Following the seizure of the monastery’s property in 1857, part of the palace was fitted out as the town hall and school of Aiguamúrcia.

According to the ideal concept of a Cistercian monastery, the rooms and outbuildings occupied by lay brothers were to have been built in this now empty space. Monks and lay brothers alike lived in the monastery, the difference between them being whether they had made a monastic profession. This difference, often determined by social origin and educational level, was particularly marked in monastic life. Monks and lay brothers took on very different tasks and even occupied separate spaces within the monastery. The monks devoted themselves mainly to study, whereas the lay brothers did the manual labour. Lay brothers were exempt from complying with all the religious duties to ensure that they could devote themselves to farm work, crafts and the maintenance required for the upkeep of the community.

The Cistercian Order delegated to the lay brothers the exploitation of the farms with which they divided the land around the monastery. These brothers achieved such a degree of specialisation that the success of the order’s farming operations in medieval times has been attributed to them.

The monastery did not have defensive walls properly speaking but was fortified by raising the height of the walls of the cloistered complex and reinforcing them with battlements. In order to protect the defenders, the gap between the battlements was covered with folding pieces of wood.

The battlements were decorated with human heads and animals sculpted into the corbels, and coats of arms that provide evidence of the people who were behind the work. The initiative to fortify the monastery originated in an order from Peter the Ceremonious following a conflict with Castile. At that time, the project could not go ahead due to a lack of resources and it was not until 1375, following a raid by Prince James of Mallorca, that Abbot Bartomeu de la Dernosa started the works.

The Royal Door was the main entrance to the enclosed monastery. It was built as part of the works to construct the Gothic cloister in the 15th century and was sponsored by James II and Blanche of Anjou, as indicated by the royal effigies and coats of arms sculpted in the arch over the door.

It is a round door with a line of large voussoirs framed by archivolts and a floriated gutter. The door was once protected by a porch, but all that remains today is the base of the arches.

The wooden leaves of the door are decorated with impressive wrought-ironwork with old metal bands, two coats of arms with four pallets, and a pair of ring-shaped doorknockers.

The cloister is one of the most significant features of Santes Creus, not just because of its artistic quality but also because it was the first Gothic cloister built in the kingdom of the Crown of Aragon.

It was constructed on the orders of James II, his intention being to create a setting worthy of what was to become the pantheon of his dynasty. James II and Blanche of Anjou not only provided the necessary resources to see their wish fulfilled, but also introduced the latest artistic trends of the time, turning Santes Creus into a beacon that others looked to for inspiration.

The works began around 1313 on the site of an older cloister, the sole evidence of which is to be found in the lavatorium. The style of the lavatorium, which is austere in accordance with the precepts of the Cistercian Order, contrasts with the exuberance of the other sculptural elements, which are notable for their innovation and quality. Similarly, the worldly theme of the capitals must have been in contrast with the Gothic paintings of religious subjects that decorated the walls of the cloister, of which bare traces remain.

The construction of the cloister was deemed completed in 1341, though interventions had to be done later on, such as the work on the tracery of the arches in 1503. The cloister thus shows a stylistic evolution between the Romanesque and the flamboyant Gothic, present above all in the capitals and tracery.

The distribution of the buildings around the cloister is in keeping with the design for Cistercian monasteries established by Bernard of Clairvaux. The church is on the north side; to the east is the armarium, the chapter house and the entrance to the dormitory, which is on the first floor; to the south, in front of the lavatorium was the former refectory, alongside the kitchen. The outbuildings that once stood on the west side, and were traditionally set aside for the lay brothers, have since disappeared, possibly due to the expansion of the cloister on this side. The cloister is, then, the centre that structures the daily life of the community. For the monks, it is a place for reading, meditation, studying, strolling or for keeping up relationships within the daily life of the monastery.

The cloister is also, however, a mortuary space, as it contains the sepulchres of various noble families, many of them linked with the conquest of Mallorca.

The cloister was built with patronage from James II and his queen, Blanche of Anjou. When the queen died in 1310, she left a bequest for the works, which were completed with contributions from James II. For this reason, their coats of arms – the fleur-de-lis of the House of Anjou and the four pallets of the Crown of Aragon – alternate among the bosses of each of the galleries.

In one respect, the cloister of Santes Creus breaks with the precepts of the Cistercian Order. Bernard of Clairvaux, the order’s leading figure, banned sculptures in monasteries and requested they be removed from cloisters. Consequently, Cistercian capitals are decorated with plant and geometrical motifs, like those found in the lavatorium and undoubtedly in the first cloister.

However, as a result of the demands of the monarchs, the rest of the capitals in the Gothic cloister offer an outstanding wealth of sculpture, both in terms of their quality and the original themes. Imaginary animals predominate, though they were one of the themes expressly condemned by Bernard of Clairvaux on the grounds that they were a distraction for the mind. Through these creatures, the artists parodied the reality of their times. This theme was not new, but it draws the eye because of the place where it appears.

Alongside these are more realistic capitals, such as the ones showing a mason or an armed knight. Even the plant decoration marks a break with the past due to the introduction of new forms.

These new models, developed in France, arrived in Santes Creus with the artists who worked on the royal tombs.

The work of a number of different craftsmen on the capitals has been identified. Those whose names we know include Francesc de Montflorit, the first to work on the capitals, Bernat de Payllars, who worked on them from 1325, and Reinard des Fonoll, the master builder and sculptor in charge of the works on Santes Creus between 1331 and 1341.

The ogee windows of the galleries are decorated with impressive traceries that vary from bay to bay as a result of the changes in style in construction work that went on until the early 14th century. The round arches and oculi formed by the traceries in the east gallery, built at the start of the project, gradually transformed as the work evolved into ogee arches, while the west gallery features flamboyant Gothic elements.

Due to damage during the 19th century, the traceries were partly reconstructed in the north and east galleries.

The cloister contains the sepulchres of the noble families linked with the monastery, in particular as a result of the conquest of Mallorca (1229). During the preparations for the campaign, Abbot Calbó granted the nobles who joined James I the privilege of being buried in the monastery. This meant that their bodies would lie in a sacred space, something that people of the time desired, as it gave them the hope of achieving divine intercession and of remaining present in the memories and prayers of the living. In exchange for this privilege, in their wills they made donations to Santes Creus that significantly increased the monastery’s wealth. At the same time, the consolidation of the relations with the nobility raised Santes Creus’ standing.

The sculptural work of the tombs is a combination of a number of styles: there are elements of the late Romanesque tradition, the iconography of the early Gothic, and even Renaissance elements such as those on the sepulchre known as the tomb of the Victorious Amazon (Guillema de Montcada). Some of these tombs are earlier in date than the Gothic cloister but were moved to their present location during the construction works. In this way, a funerary space befitting the nobility was created near the church but still at a distance from the royal pantheon.

The pictorial traces on the walls of the cloister indicate that they were decorated at one time, though few images have been preserved. Above the door of the former Chapel of Sant Benet is a fresco of the Annunciation. The work is attributed to Ferrer Bassa and dates from around 1340, a time when construction work on the cloister was drawing to a close.

The painting is badly damaged and only a third of the complete work has survived. The colour has faded and parts of the figures of the Virgin and the angel have disappeared. The outline of the architectural frame around them has also been largely lost.

Above the Mongia Door, through which the monks entered the church, there is a polychrome sculptural group in alabaster that refers to the Last Judgement. The group, dating from the 14th century, consists of Christ in Judgement, three angels and a monk in prayer, identified as Abbot Francesc Miró (1335-1347). Three angels carry the instruments of the Passion: the lance and nails, the cross and crown, the reed and sponge, and the container of vinegar.

The polychrome of the corbels on which the figures rest has been preserved. The sculpture depicts the symbols of the four Evangelists and the resurrection of Adam and Eve.

Above the niche of the Montcada family, there is a Gothic image of the Mother of God and the Infant Jesus. Above it is a small canopy and it rests on a corbel with two angels.

There are two doors that lead off the cloister into the church. The monks entered by the Door of La Lliçó, situated closer to the apse, while the lay brothers used the door close to the far end of the church. This door took them to the place they occupied in the church.

From the cloister, you can see the dome that crowns the church. In the case of Santes Creus, the dome is purely ornamental in function, since it does not allow light to enter the nave. It is at odds with the architectural austerity of the Cistercian order and is explained by the desire of James II, who paid for its construction in the early 14th century, to embellish the church.

The technical solutions employed are innovative and the dome of Santes Creus introduced a type of construction followed by other monasteries and convents in the order such as Poblet and Vallbona de les Monges.

In the mid-18th century, a lantern with glazed tiles was added. It now serves as a bell tower.

A small edifice extends off to the side of the south gallery of the cloister. This houses the basin where monks washed their hands before entering the refectory. According to the ideal plan of Cistercian monasteries, the lavatorium would be situated in front of the refectory.

Hexagonal in floor plan and roofed by ribbed vaulting, the lavatorium is notable for the austerity of its decoration, featuring geometrical forms and plant motifs. These elements, which are in contrast with the rest of the sculpture in the cloister, define the lavatorium as a building in the purest Cistercian style and are testimony of the early phase of construction of the monastery.

In the centre of the lavatorium is a circular fountain with a white marble upper bowl and several channels through which water flows. After working in the vegetable garden or out in the fields, the monks would wash their hands before entering the refectory to eat. Consequently, a hand basin was always placed in front of the refectory.

In front of the lavatorium is a door that, in accordance with the guidelines for Cistercian architecture, must have led to the old refectory. Alongside it, there would have been the kitchen and the cellar, which has also disappeared. Even though nothing of the refectory has survived, documentation reveals that Queen Blanche of Anjou provided a legacy in her will for it to be constructed.

All that remains now is a long room that must have served as a cellar, where original 17th-century barrels are now kept. Following the seizure of Church property, this was one of the spaces that were sold. While the lower part continued to be used as a cellar, on the upper floor homes were built for workers.

This space is now given over to the scenic and audio-visual montage entitled The World of the Cistercians.

One of the daily rituals of monastic life took place in the chapter house, the reading of a chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict. The chapter house is one of the most significant rooms in a monastery due to the importance of its function, and in the case of Santes Creus, it is one of the most outstanding rooms at an architectural level. This space is part of the first section to be constructed, dating from the 12th century, and is notable for its austerity, simplicity and balance.

The monks sat on the tiered seats against the walls, while the abbot, the spiritual father of the community, sat below the central window and presided over the meeting. There he would instruct the monks on moral and religious issues following the reading of the Rule and the Martyrology. Pressing issues related to the daily life of the community were discussed and public confessions were made here. Appointments to various posts in the monastery and voting for a new abbot were also held here.

The entrance door forms a round arch with archivolts and, within it, forms twin arches that are also round. The same structure is reproduced in the windows on either side. Through these openings, the lay brothers outside were able to follow the abbot’s teachings.

The ceiling of the room consists of nine groined vaults, constructed by the crossing of round arches. The ribs of the vaults converge in four stone columns, reproducing the form of a palm tree.

The sculptural decoration is characteristic of the order and consists of plants familiar to the monks or typical of the areas where they built their monasteries, such as laurel leaves and palmettos. There are also some more unusual decorative features, among them two croziers opposite each other and the representation of four palmettos in a cross and a Solomon’s knot.

Set into the floor of the chapter house are seven gravestones marking the burial places of a bishop and six abbots. Like the other members of the community, the abbot was expected to be buried in an anonymous and humble manner. These people, however, were influenced by the Renaissance cult of individualism and chose to be interred in a privileged space worthy of their importance and underlining their status through their gravestones.

The chapel occupies the space of the monastery’s former armarium, where the books used in the chapter and during reading sessions in the cloister were kept. In 1558, it was converted into the funerary chapel of Magdalena Valls de Salbà, the sister of Abbot Jaume Valls. The works were paid for by a bequest that Magdalena herself left in her will.

The chapel occupies the space of the monastery’s former armarium, where the books used in the chapter and during reading sessions in the cloister were kept. In 1558, it was converted into the funerary chapel of Magdalena Valls de Salbà, the sister of Abbot Jaume Valls. The works were paid for by a bequest that Magdalena herself left in her will.

As she stipulated in her will, Magdalena Valls’ tomb is watched over by a sculptural group on the Assumption of the Virgin. Abbot Contijoc commissioned the work from Perris d’Austri, a French master religious image maker who lived in Tarragona.

The work was badly damaged during periods of vandalism in the 19th century and originally consisted of ten apostles around the recumbent Virgin and by a relief depicting four angels raising the body of Mary up to heaven. Traces of polychrome have survived. These were the work of Cristòfol Alegret, a painter from Cervera, who was employed to gild and paint the sepulchre of the Virgin and part of the chapel.

Work began on the construction of Santes Creus church in 1174. Even though the works continued until the early 14th century, it opened for worship in 1211. The church, dedicated to Mary, Mother of God, as is the custom in the Cistercian order, was for the private use of the community. It was not until the seizure of Church property that it took on the role of the parish church, which the Church of Santa Llúcia had previously been.

It is built on a Latin cross and has a nave and two aisles divided by sturdy columns that support a roof consisting of ribbed vaults. The apse is four-sided and has two smaller chapels on each side. In keeping with Cistercian canons, the church is austere in appearance, though there is the occasional concession to the monarch’s desire to build an impressive monument, such as the Gothic window or the dome.

The monks gathered in the church for the services that structured their daily lives. The Cistercian monk’s day begins before dawn with Matins. When the sun comes up, Lauds is held, a song of praise to God. Then came Prime and Terce, followed by Holy Mass, Sext and None. Once the work of the day was over, Vespers is celebrated and then Compline at night.

When the Cistercian Order was founded, it was agreed that every monastery would have the same books for the Divine Office and mass. To accompany the ritual, they adopted Gregorian chant but rejected vocal ornamentation and polyphony. However, musical instruments were introduced in the 14th century and in 1486 the organ was admitted.

The community kept the relics donated by James II and Blanche of Anjou in the church. These included the tongue of Mary Magdalene, a popular object of veneration. During the celebration of her feast day, the abbot put the saint’s tongue into the water jars of the faithful to bless them.

The high altarpiece was commissioned by Abbot Pere Salla in 1647 from the sculptor Josep Tremulles. The intention was that the new work would replace the previous Gothic altarpiece by Lluis Borrassà, which has been divided between Tarragona Cathedral and the National Museum of Art of Catalonia. Neither of these two altarpieces meets the requirement for austerity or the ban on images established by St. Bernard on the founding of the order.

Tremulles’ work is dedicated to Mary, Mother of God, who is surrounded by St. Benedict and St. Bernard, alongside two saints in the order.

Concealed behind the altarpiece is a large rose window measuring 6.3 metres in diameter. Even though rose windows were a common feature of church façades, the Cistercian Order also used them as a decorative element in apses.

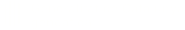

The rose window dates from 1193 and, apart from the central rosette, it retains much of its original stained glass, today regarded as one of the oldest of the Cistercian type.

One of the most impressive features of the church of Santes Creus is the royal tomb of Peter the Great and that of James II and Blanche of Anjou.

Peter the Great had asked to be buried the monastery in keeping with the custom of being buried near holy places in order to enjoy from spiritual benefits. Influenced by this decision and by the family pantheons he had seen in Sicily, his son James II decided to build a royal pantheon here that would demonstrate the authority of his house. It was this that made him commission a new sepulchre to honour his father and to which Peter’s remains were moved in late 1302 or early 1303.

The project for the royal pantheon was a vehicle for royal propaganda: its magnificence was intended to convey the power of the crown. James II hoped to bring the sepulchres of all his descendants together in Santes Creus to demonstrate royal power. His initiative proved to be in vain, however, as his heirs chose other places to be buried.

The importance of the message that James II wanted to convey with the pantheon is reflected in the care that went into the design and the selection of materials. In the case of the tomb of Peter the Great, the work drew sculptors from northern France who were familiar with the most innovative trends, which arose in the mid-13th century in the Île-de-France area. These contributions resulted in a new format for columns, a new type of capital and new plant motifs, which are present on the two royal graves and in the cloister.

The Sicilian influence is also evident in the choice of materials such as porphyry, a prestigious stone that could only be obtained in the 13th century by recycling older elements because the quarry had been closed. For example, the body of Peter the Great is in a Roman porphyry bathtub that James II acquired to turn into his father’s sepulchre, following the example of Frederic II of Sicily. Other stones used in addition to porphyry are white marble and blue marble, which was quarried in Girona.

The mausoleum still bears abundant paint, with three colours predominating: blue, red and gold. Restoration work has confirmed that it is the original polychrome.

In the case of the sepulchre of James II and Blanche of Anjou, the funerary monument consists of a double tomb with a pitched cover. Inspired by the royal pantheon in Saint-Denis in Paris, it features images of the recumbent monarchs. The tomb was altered in the 16th century, with the addition of three alabaster plaques. One of these plaques was ripped off in 1836 during an attack on the royal pantheon following the seizure of the monastery’s property. The tomb of James II and Blanche of Anjou was profaned and their bodies removed, chopped up and paraded around the nearby area. In contrast, the tomb of Peter the Great remained untouched, making it the only funerary monument of the monarchs of the Crown of Aragon that has survived intact to this day.

In the light of this remarkable fact, when the restoration of the royal pantheon began in 2010, an exhaustive study was conducted that included the construction of the tombs and an anthropological study of the bodies and the funerary rituals.

At the foot of the mausoleum of Peter the Great, there is a slab over the tomb of Roger de Llúria, who had expressed a desire to be buried at the feet of the king he had served. In his position as admiral of the Catalan fleet, he defended the monarch’s interests in the kingdom of Sicily.

This staircase links the church with the monks’ dormitory. Its purpose was to enable monks to descend for prayers such as Lauds, when the sun rose, or Matins during the night. In addition, monks used it to go up to the dormitory after Compline at the end of the day.

To the side of the church is the 18th-century wooden box that conceals the clock machinery. It was connected to the former bell tower, known as the Tower of the Hours, and reminded the community of the times of the Divine Office.

The front of the box still bears the polychrome that depicts a large compass. Each of the four corners of the front is decorated with a representation of a wind, shown as the face of a person blowing, and below the circumference, in the centre, there is the head of a monstrous person done in red. Around the compass, the circumference is divided into 24 hours. In these early clocks, the face is of little importance because what mattered was the machinery that operated the bells that marked the rhythm of the community’s life.

The church of Santes Creus contains an exceptional collection of Cistercian stained glass dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, some of which are still the originals. The compositions follow the designs typical of the Cistercian order, featuring intertwining geometrical shapes done in pale colours, with only small details in green and red. The windows also contain numerous motifs done in grisaille.

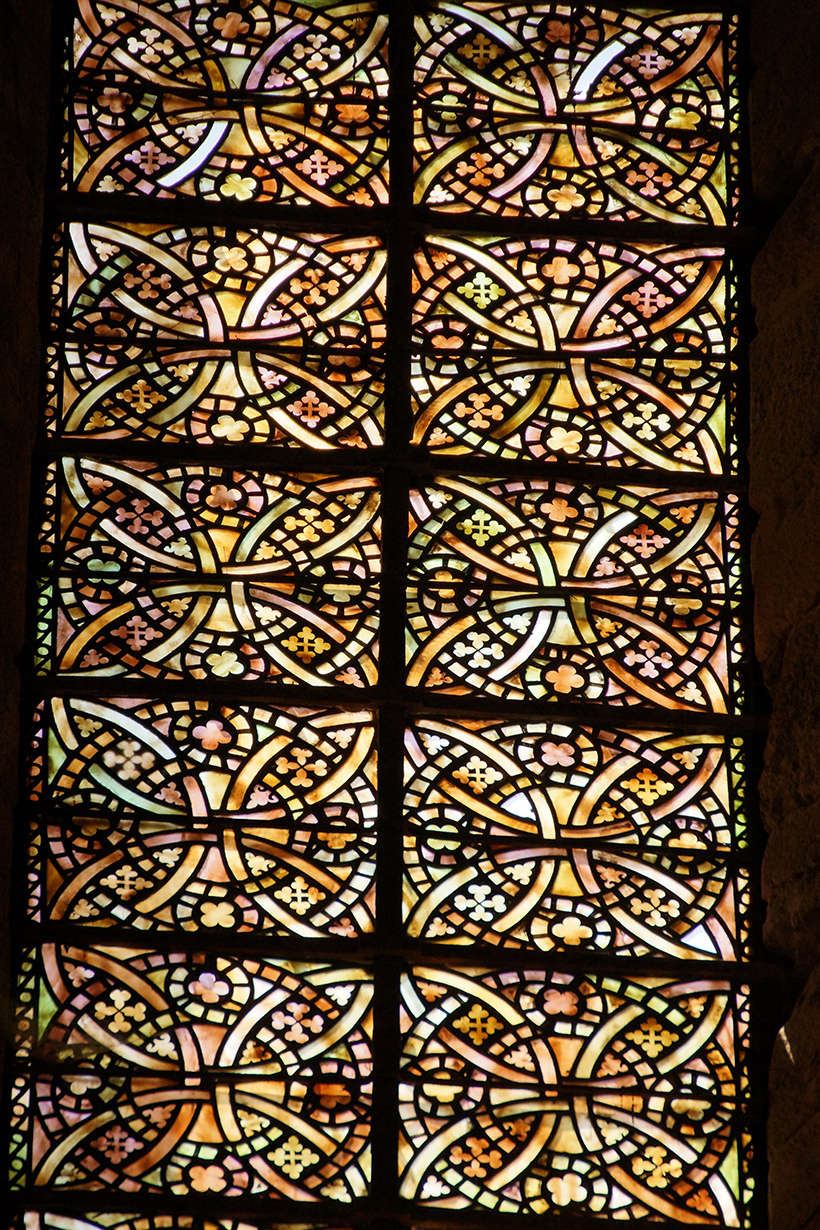

The large Gothic window in the façade, made around 1300, is an exception to the Cistercian Order’s typically austere architecture, and it has been interpreted as one of the examples of the embellishments of the monastery made by James II and Blanche of Anjou as part of their initiative to turn Santes Creus into the pantheon for their royal house.

The glass features lavishly coloured stained-glass works on the life of Jesus. The various scenes are divided into 48 small forms organised by means of four columns, each of which tells the story of one of the Evangelists.

The stylistic analysis of the figures and the historical documentation indicates that these Gothic stained-glass windows are the oldest in Catalonia and predate the constructions of the large Catalan Gothic glass-works.

This mausoleum was commissioned by the Duke of Medinaceli i Cardona, Luis Antonio Fernández de Córdoba, as a burial place for the mortal remains of his wife, Teresa de Montcada i Benavides, and the remains of members of the Montcada family buried in Santes Creus. Teresa de Montcada died in 1756 and was the last representative of the Montcada family in Catalonia, since her lineage was added to the rest of the titles of the House of Medinaceli.

The sepulchre is the work of Josep Ribas, an architect from Barcelona, who was employed to undertake it in December 1757. The tomb is a sepulchral vessel made of brown jasper from Tortosa, framed by a round arch made of rectangular pieces of black marble from the Charterhouse of Escaladei. In the place of the keystone of the arch hangs the coat of arms of the Medinaceli family.

The parlour connects the main cloister and the rear cloister. It was a thoroughfare but also a meeting place, as demonstrated by the stone benches up against the wall that were formerly lined with wood to make them more comfortable. The monks were able to hold brief conversations here, though always prudently, since the Cistercians lived in silence as they believed in its spiritual benefits.

Because of its location, the parlour funnels the wind and this combined with its excellent acoustics, making privacy impossible, mean this space is not very hospitable, nor does it encourage long talks.

Santes Creus has a second and more artistically simple cloister that structures the outbuildings situated at the rear. It was built in the second half of the 14th century, during the time of Abbot Guillem Ferrera, in order to provide some order to this area and to connect the abbot’s palace with the rest of the monastery.

The premises around the cloister, in addition to the palace, were the infirmary, the Chapel of the Holy Trinity and the oldest constructions, which had been refurbished and were still in use.

This area evolved as the years passed, adapting to the needs of the community at any given moment. The refurbishment work of the 18th century had the most impact, significantly altering the surroundings. It was at this time that the refectory was refurbished (1733) and a new infirmary was built alongside the cloister (1736). The project also affected the configuration of the cloister. Whereas originally it had consisted of solely a ground floor and a wooden roof, in the 18th century another floor was added above the cloister gallery. Very little has survived of this second floor, such as the windows in the infirmary gallery.

During the Third Carlist War, this area was severely affected by the intervention of the residents of Vila-rodona, who needed wood and stone to fortify their town from a possible Carlist assault. As a consequence, the structures were weakened and gradually collapsed for lack of restoration. Now consolidated, these remains are evidence of the difficulties of the period that spanned the monks’ expulsion and the conversion of the monument.

The cloister courtyard is an example of the conversion of Santes Creus into a monument, which followed a harsh period during which some of structures were damaged. In the early 20th century, the Mancomunitat (the Commonwealth of Catalonia), a federation of the four Catalan provincial councils, promoted the restoration of this courtyard, which was at that time being used as a vegetable garden by the caretaker. Jeroni Martorell was commissioned to design a landscaping project, though work did not begin until 1930, when cypress trees, donated by Eduard Toda, and other species were planted.

One of the tasks undertaken by medieval monasteries was to copy manuscripts and to draft documents. Cistercian monks also engaged in this work but St. Benedict laid down restrictive rules to preserve the order’s austerity by reducing the range of colours, limiting ornamentation to capital letters and eliminating figurative elements. Even so, the order also produced lavishly illuminated manuscripts when these precepts were relaxed.

The main task was to copy the texts crucial to monastic life, such as the Gospels, the Customs and the Bible. This work kept the scriptorium at Santes Creus busy until the 16th century, when the arrival of the printing press led to a decline in its activity. At this time, the library was moved to the floor above and the space was used to enlarge the cellar.

The room used as the scriptorium was built during the first phase of construction of Santes Creus, which was characterised by the thickness of the walls, the austerity of the decoration and the roughness of the architectural features. Nowadays, it is used to screen the audio-visual presentation entitled The World of the Cistercians, and is only open to visitors for this purpose.

A small door leads into the prison cell, a cramped and damp space used as punishment and penitence cell by the brothers. The abbot needed to know the most appropriate way to correct the behaviour of his monks and would even consider the possibility of physical punishment. In the most extreme cases, he might even contemplate a prison sentence.

This cell could also be used as a way of imprisoning captives. Consequently the prison could be used to gaol the prisoners of the Crown while they were being moved from one city to another, or even convicts sentenced by the abbot, as he held full jurisdiction over most of his domains, meaning that he had the duty to maintain order and the right to administer justice.

Some graffiti that have survived provide evidence of the use of the prison cell to punish monks. On the ceiling you can see writing, and at the height of the second floor above the entrance door, there is a wall painting with a Crucifixion. You can make out Jesus on the Cross and the two crucified thieves on either side of Him. The dates of the inscriptions indicate the cell was used during the second half of the 16th century.

The construction of a new refectory meant that the kitchen had to be moved so that it was next to the monks’ dining room. Most of the roof over the room has disappeared and there are few elements that make it possible to determine its original function. The surviving remains include the water conduits and the basins, a table and a stone hearth where pots were placed over the heat. There is also a hand mill and the remains of millstones from a flourmill.

Hidden in one of the walls are ancient water pipes. Enormous basins made from large blocks of stone, in all likelihood the kitchen sinks, have also survived.

The use of water was a crucial issue that the Cistercians resolved by installing the necessary infrastructure. In Santes Creus, the monks built an underground channel to send water from Sant Sebastià Wood to the monastery, where it supplied the lavatorium, the latrines and the kitchen. The channel passed under the kitchen and continued on to the upper mill and the irrigation water cisterns and from there on to Vila-rodona.

The serving hatch is an indication of the functionality built into Cistercian constructions. In order to facilitate the community’s daily life, the kitchen and the refectory are situated next to each other, and the hatch enabled dishes to be passed between them.

The refectory of the rear cloister appears in documents dating from the 16th century, though its appearance today is due to works done in 1733 to allow more natural light to enter by raising the ceiling and opening up two additional windows, one at each end, above the cloister galleries.

Benches and wooden tables used by the monks were arranged around the perimeter of the room. While they ate in silence, one of the monks would read from religious writings. The monks took turns to read during meals. Similarly, the monks charged with serving food to the other brothers changed on a weekly basis and none of the members of the community were exempt from this task.

The food served varied according to the time of year. In winter, the kitchen prepared a hot dish and in summer more salads were made. The monks’ diet was determined by the stipulations of the Rule and the need to be self-sufficient. The basis of their meals was legumes, vegetables and fruit from the monastery’s vegetable gardens and orchard. A portion of bread and a little wine, normally watered down, were served with meals. The diet was complemented by fresh or salted fish, eggs and homemade cheeses. Meat was not permitted, though the Rule did allow for exceptions in the case of illness. In 1481, the Cistercian Order gave a general dispensation, again as an exceptional measure, due to the high price of fish.

The works to fit the room out as a dining room included a ceramic frieze around the walls as a back for the benches, and panels set into the floor. The decorative motifs of the tiles are in keeping with the styles of the period.

The palace was the abbot’s residence and the centre of the administration of the monastery. The functions of the abbot of Santes Creus were not confined to the spiritual guidance and governance of the monastic community, as he also had duties as a feudal lord and a Church representative of the Corts (Catalan Parliament). In addition, for a very long time he enjoyed a close relationship with the Crown thanks to the fact that the abbots of Santes Creus also held the title of Royal High Chaplain. By virtue of his position and authority, the abbot was obliged to maintain constant contact with the outside world, justifying his need for a residence of his own, through which he was also able to express the power of the monastery.

The first palace at Santes Creus was situated at one end of the rear cloister, giving it direct access to the outside. The building continued to fulfil this use until the 16th century, when the abbot’s residence was moved to Plaça de Sant Bernat.

An impressive example of the Gothic palace, the building is not uniform in style due to the remodelling work it underwent on a number of occasions over time, with additions made that demonstrate the monastery’s strength beyond medieval times.

The structure of the building was determined to a large extent in the second half of the 14th century, when an ambitious refurbishment project was set in motion by Abbot Guillem Ferrera (1347-1375), affecting the rear part of the monastery. In addition to the cloister, the façade of the palace and its main courtyard were built at this time, leaving the complex arranged around two contiguous courtyards.

The main courtyard, the only part of the palace currently open to visitors, is the determining feature that structures the connection between the entrance courtyard, the rear cloister and the main floor of the palace. In keeping with the structure of Gothic palaces, an exterior staircase leads up to the main floor, where the abbot lived, while the upper rooms were given over to services. The quality of the decorative elements, gradually introduced by a number of abbots, makes it the most notable space in the palace.

Two porphyry columns are built into the construction of the palace. According to documents, James II brought them from Sicily, along with the bathtub, to form part of the royal sepulchre of Peter the Great. Following the decision not to include them in Peter’s tomb, they were the source of a dispute between Peter the Ceremonious and Abbot Ferrera, who decided to use them to enhance the prestige of the palace.

The palace has a second courtyard, currently closed to visitors, which communicated with the outside world via a large gate. Possibly for reasons of security, the rooms, outbuildings and galleries around it were not directly accessible from this courtyard, which only communicated with the stables, the former keep and the main courtyard.

Once the Cistercians had decided to settle in these lands on the bank of the Gaià River, the community from Valldaura would have erected these temporary buildings for use while the basic rooms of the monastery were being constructed. These building were later remodelled and remained in use till the monks were expelled. It is known that there were buildings with coffered ceilings made of wood and plaster in the 16th century.

All that is left now, however, are stone arches and vestiges of the old walls. In September 1784, the residents of Vila-rodona were granted permission to remove demolished material from the monastery so that they could hurriedly fortify their town in the face of a possible Carlist attack. Even though the permit referred to rubble, the east gallery of the rear cloister and the surrounding buildings were knocked down.

Situated in the rear part of the monastery complex, the Chapel of the Holy Trinity was undoubtedly the community’s first church from the time it moved into Santes Creus in the 12th century to the opening of the main church for worship in 1211. Subsequently, when new outbuildings were constructed in the rear cloister, it was turned into the infirmary’s chapel.

It is in keeping with the style of many churches of the late 12th century, as it is small in size, is built on a rectangular floor plan, has no apse and is roofed by slightly pointed barrel vaulting.

The stone used in the building is clearly different to that employed in the rest of the monastery, and consists of travertine, a lightweight material that is less durable and hence is more susceptible to erosion.

In the chancel of the Chapel of the Trinity is a wooden carving of Christ Crucified, made in the 15th century by an Italian-influenced school. The piece is damaged and no longer has the cross. The figure of Christ has lost its arms and legs below the knees. Following its restoration, it was placed in this spot, though the location of its original sitting is unknown.

Retired monks who had been in the community for more than 40 years and elderly monks lived in especially adapted homes built in front of the palace, on the opposite side of the cloister. Very little evidence remains of this construction, though an impressive long and very flattened Catalan or segmental arch has survived, despite the destruction caused during the Third Carlist War (1872-1876).

The origins of this building go back to the refurbishment work begun on the monastery in the 17th century in order to reorganise the community’s living space. This new construction would have housed stores for clothing and washing-places on the ground floor, while the upper floor was given over to the infirmary.

Materials of lesser quality were used to construct this building. No large blocks were employed but small pieces of unevenly cut stone that had earlier been rejected or which were reused. In addition, adobe was used in the construction of the arches on the second floor, built during refurbishing carried out in the 18th century.

Like other buildings in this area, the infirmary suffered severely from the devastating effects of the expulsion of the monks from the monastery. In 1930, however, reconstruction work began as part of the efforts to protect Santes Creus, which had been declared a national monument in 1921. The aim of this work was to adapt the monastery to house artworks and a small museum, although this project was not completed due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

In 1575, Abbot Jeroni Contijoc ordered the construction of the Tower of the Hours for the bells that are operated by the church clock machinery and which ring to mark the rhythm of monastic life.

The mason Joan Roig and the master house builder Joan Casquilles, from Vila-rodona, were commissioned to build this four-sided tower with four sections divided by cornices. Three of the four gargoyles at the corners at the top have survived.

At the level of the dormitory, the tower housed the archive where the privileges of the monastery, any donations received and ledgers were kept. Following the monks’ expulsion, the documentation was saved by private individuals and finally distributed between the National Historical Archive, set up in 1866, the Archive of the Crown of Aragon and the History Archive of the Archdiocese of Tarragona.

The cemetery is indicated by a single stone cross, as the Cistercians did not permit elements that would distinguish between the members of the community.

Like every event in the life of the community, death had its own ritual as well. In the monastery of Poblet and the convent of Vallbona, both of them Cistercian communities, there was a documented custom of announcing the death of a monk or nun by knocking three times with a piece of wood in the cloister. A ritual was then set in motion, during which the body was undressed, washed and then clothed again in the Cistercian habit. Once prepared, the corpse was then moved to the church, where the community kept vigil over the body and the funeral rites were performed.

The body was then taken out of the church through the Door of the Dead to the cemetery, where it was deposited, without a coffin, in a grave dug out of the earth. The body was laid out looking eastwards with its hands crossed over the chest, and the cowl of the habit concealing the face.

A large number of stonemasons’ marks have been preserved in the walls of the main church. These are simple symbols used to identify the blocks of stone worked by each craftsman or workshop and to calculate the cost of the work done. If the mason had not received payment, as the construction advanced, the blocks were placed with the mark facing outwards. The symbol was thus visible, making it possible to enter each person’s work into the accounts. In cases where payment had already been made, the way the blocks were laid was of no consequence and many of the marks remain hidden on the faces inside the walls.

The dormitory was included in the first phase of construction. Work on it began in 1191 and was completed in 1225, though some historians suggest that the construction could have continued in a second phase that ended in the second half of the 13th century.

In keeping with the Cistercian ideal, the dormitory is situated above the chapter house and the locutorium or parlour. To get to and from the dormitory, monks were able to use two staircases: one that linked the dormitory and the cloister; and the other, known as the night-time staircase, which took them directly into the church to attend prayers at night.

The most interesting aspect of this room is that the builders succeeded in creating a large space without columns or pillars to support the roof thanks to the eleven slightly pointed diaphragm arches. These arches rest on the thick walls and support a pitched roof made of wooden beams, fired clay bricks and tiles. Large windows were opened up between the side arches along the length of the dormitory during later refurbishment work.

The width of the room is such that all the monks could be accommodated, as the Rule stipulated that they were all to sleep in the same room on a straw bed and fully clothed. Over time, individual cells and the first beds with straw mattresses were allowed. These cells gradually became more common in Santes Creus from the 14th century onwards and were established in all Cistercian monasteries in the 16th century.

The dormitory staircase also led to the library, which is currently not open to visitors. It has been calculated that the library would have contained some 3,000 to 4,000 volumes, among them 200 manuscripts dating from the 13th to the 15th century. Following the seizure of Church property, the library’s holdings, as well as the legacy from other monasteries, were used to found the Tarragona Public Library.

La visita al Reial monestir de Santes Creus permet descobrir un monestir que destaca per seguir amb gran fidelitat l'estructura arquitectònica concebuda per Bernat de Claravall per al monestir de Clairvaux al segle XII.

La clau que defineix aquesta arquitectura n'és la supeditació a les exigències de la vida monacal. Els espais estan pensats per complir una funció i s'ordenen per facilitar al màxim la senzilla vida dels seus habitants, marcada per unes normes que regulen tasques i horaris i que defineixen l'aïllament del món.

Els monjos cistercencs viuen apartats i, per això, el monestir té un recinte tancat en ell mateix, anomenat clausura. S'hi troben tots els espais clau per la vida del monjo. Tant és així que, resseguint les estances, se'n poden redescobrir les pautes de vida. A Santes Creus, a més, la disposició d'aquestes dependències es caracteritza perquè segueix amb una gran fidelitat el plànol ideal de sant Bernat.

Malgrat tot, el monestir no era un ens aïllat. La comunitat mantenia una relació habitual amb els habitants dels seus dominis feudals per a afers derivats de l'administració de les seves propietats, per cobrar les rendes o per impartir justícia. A més, el vincle feudal obligava els vassalls a emprar determinats serveis que el monestir posseïa en monopoli, com ara el molí, el forn o la farga. Així, la ferreria es trobava dins el mateix complex, mentre que al voltant del monestir hi havia dos molins fariners. Igualment, els preceptes de l'orde marcaven l'obligació d'acollida, especialment de pelegrins, que arribaven a Santes Creus atrets per les relíquies de Maria Magdalena, un culte que va tenir molta popularitat entre els segles XIV i XV.

L'espai per desenvolupar aquestes funcions es concretava en dos recintes més, al marge de la clausura. El primer, obert a tothom, acollia la porteria, la parròquia i els serveis. El segon, amb un accés restringit, era l'espai de relació dels monjos amb l'exterior, on hi havia l'hostatgeria i les dependències d'administració.

Si bé totes aquestes estructures responen als cànons cistercencs, Santes Creus també amaga sorpreses. El vincle amb la Casa Reial el converteix en un lloc excepcional. La voluntat dels monarques que Santes Creus fos un lloc majestuós per acollir el panteó reial implicava la introducció d'estils trencadors amb l'austeritat cistercenca. D'aquí, el contrast entre la senzillesa de l'església i l'escultura de les tombes i del claustre, o entre els vitralls de les naus laterals i els del finestral gòtic de la façana. Els monarques van imposar el seu criteri per sobre de les normes de la comunitat. Aquest impuls innovador comportà que a Santes Creus s'aixequés el primer claustre d'estil gòtic de la Corona d'Aragó.

De la mateixa manera que els monarques van utilitzar el claustre i les tombes reials com a expressió del seu poder, en diferents indrets del recinte es troben detalls arquitectònics i escultòrics de diferents èpoques que donen testimoni del poder que el monestir va mantenir fins a la seva desaparició, al segle XIX.

accessibility | legal notice and privacy policy | cookies | © Departament de Cultura 2018 Agència Catalana del Patrimoni Cultural