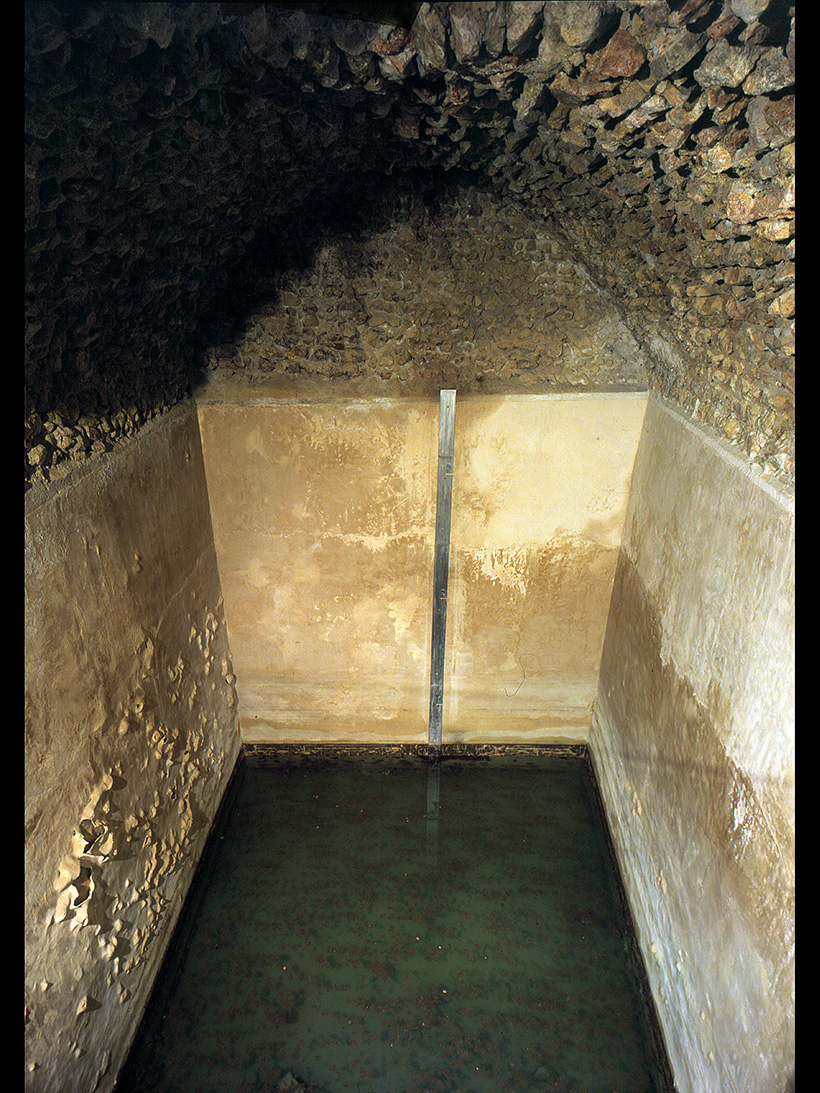

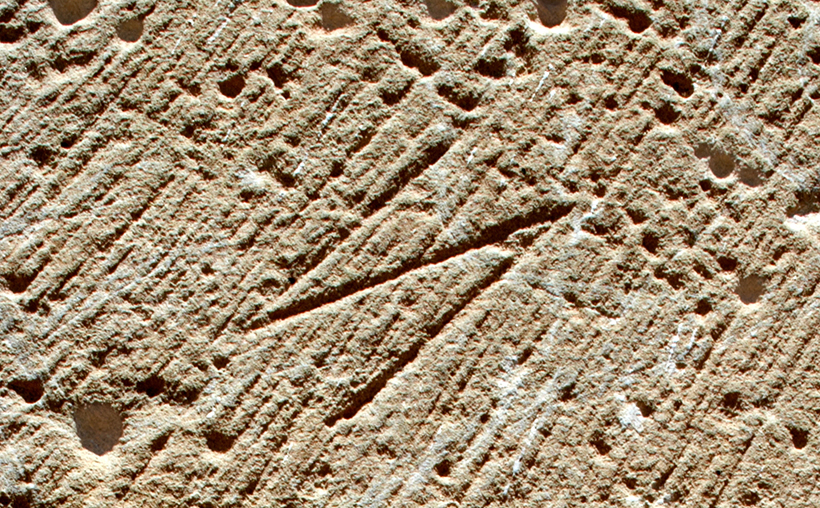

Miravet Castle stands on a rock, protected by the sheer drop down to the river below and by 25-metre-high perimeter walls. Where the car park is now, there was once the fosse which defended the fortress on the north side. It was made by means of a broad, deep cut into the mountain rock parallel to the wall. The purpose was to make it as difficult as possible to approach. Evidence of the work of opening the fosse on the cliff is provided by the marks left by the cutting tools in different parts of the slope. The stone that was taken from here was used to build the castle, so that the fosse also served as a quarry.

The entrance is a weak point in the defence of any castle, consequently it is reinforced by a series of architectural structures intended to protect it, such as towers and a barbican. The approach road skirts the walls, following a meandering course that prevents a frontal attack and forces attacking enemies to place themselves within range of the defenders in the towers.

This tower, which has evidently been remodelled on numerous occasions, was built by the Templars on top of the old walls dating from the time of the Moors and was erected to strengthen the defences on the north side. Its forward position is crucial for controlling the entrance gate below.

The existing entrance gate to the castle dates from the 17th century. Built of smaller, more irregular blocks of stone, it differs from the large ashlars used in the Templar construction that can be seen in the Treasure Tower.

The lower bailey is an enclosure that was given over to the services required for the day-to-day running of the castle. Its 12,000 m2 contained stores, stables, animal pens and yards, workshops, a water cistern and even vegetable patches and fruit trees. Most of these features left no physical evidence of their existence due to their impermanence, but we know of them thanks to descriptions given in documents.

This building, situated in the lower bailey, has been used for various purposes over the course of its history. It was constructed during the time of the Templars, as shown by the blocks of stone and the decorative band that has survived on the lower part of the wall. However, we do not know what it was used for at that time. In the 15th century it was used as stables, though it could also have housed other animals, since it is described in some documents as a cow barn. When it was used for stabling animals, the staircase was replaced by a ramp. The floor of the building was later excavated to make it level with the door, leaving the feed troughs suspended.

This area originally consisted of stepped terraces that followed the slope of the mountain, but in the 16th century the land was filled in to level it and a new wall was erected.

In the 17th century, work began to adapt the old medieval walls to the needs of modern warfare, in which artillery predominated. The only defence against the destructive force of cannons was to make the walls thicker, meaning that it would take assailants longer and more ammunition would be required to demolish them.

The south terrace is the result of 17th-century modifications to strengthen the defences on this side. The wall is not as sturdy here, possibly because it was only intended to reinforce the effect of the natural drop.

The various alterations made in the 17th and 18th centuries include the construction of this bastion situated at the corner of the south and east wing of the upper bailey. The bastion stands forward of the walls, covering a larger area and eliminating blind spots for defenders.

From here, you can see that the upper bailey is a fortified enclosure within the castle. The only entrance is this gateway. The other openings are small and high up. The gate was protected by a ditch and guarded by the gatehouse inside the passageway.

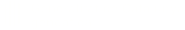

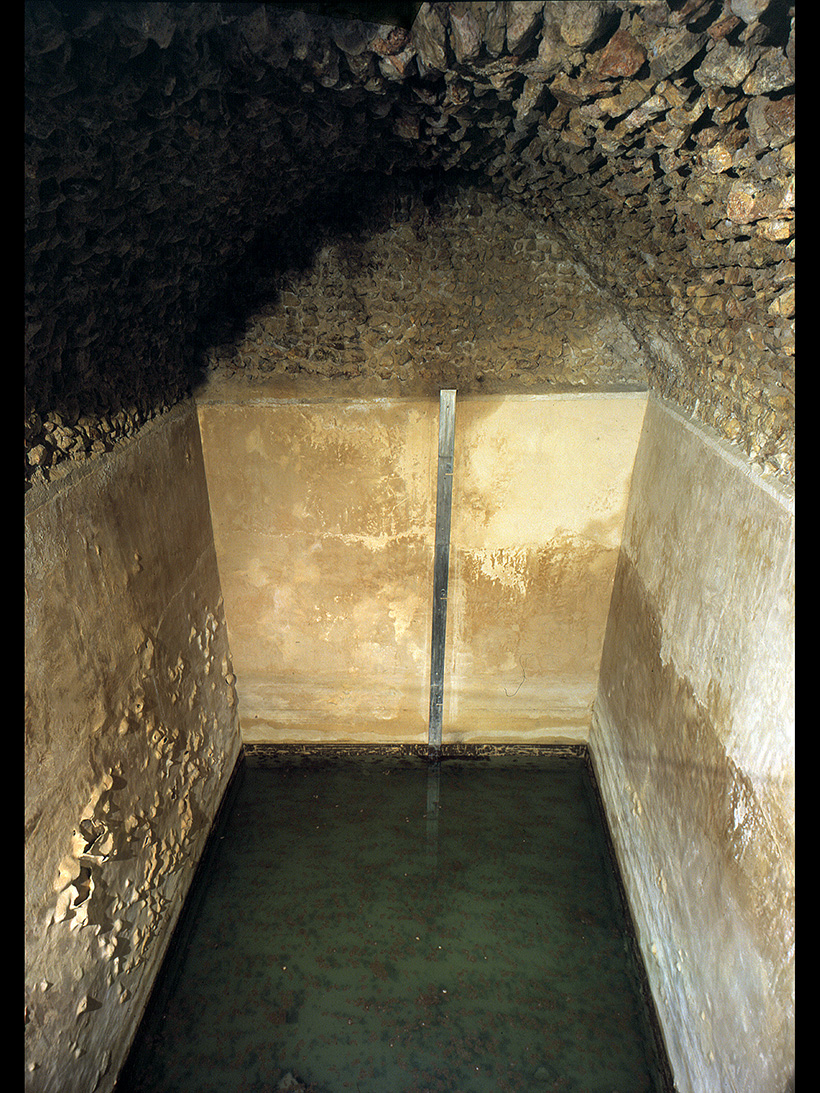

To one side of the entrance passageway and partly excavated into the ground is a cistern built during the time of the Moors that has remained in use through to the present day.

The upper bailey was the residential part of the castle. It consists of a fortified area, the only entrance to which is via a covered ramp that leads to the courtyard. The arrangement of the buildings to form four wings around a courtyard creates an enclosed space protected from the outside by the walls of the buildings and by the five defensive towers.

The inner court is central to the structure of the upper bailey: the Templars constructed the community's outbuildings around it, creating an enclosed space. These works were done between the close of the 12th and the 13th century in the late Romanesque style.

This space has undergone numerous changes over the centuries. It is now identified as a kitchen as records show that it was used for this purpose at one time.

The refectory was the Templar community’s dining room. The Rule insisted on readings of the holy scriptures during meals and eating in pairs to ensure austerity and poverty. The discipline of the Rule also imposed abstinence and fasting although, unlike in other monastic orders, meat could be eaten three times a week because of the requirements for good physical condition imposed by the military character of the order.

Every fortress had storehouses for oil, wine and grain to ensure that the occupants could survive a siege. The most notable feature of this space is the two silos dug into the ground.

Even though this room is described as the cellar, it has served a number of different purposes over the course of time. As well as being used as a cellar, it has also been a storeroom, stables and even a prison at some point in its history.

The gallery, which has barrel vaulting and is known as "De profundis", is the antechamber to the church and is on the first floor of the main building. It is reached from the inner court by the stone staircase, since there is no direct internal communication between the floors. Thanks to restoration work, the large windows and portal with round arches have been reinstated, as has the original red colour of the floor, the result of mixing powdered pottery with lime mortar.

As well as the daily service, after Sunday mass the church was used to convene the chapter, where different matters were discussed: administration of the commandery, confession and penitence for the members of the community or the ceremony for new members joining the order.

Miravet Castle stands on a rock, protected by the sheer drop down to the river below and by 25-metre-high perimeter walls. Where the car park is now, there was once the fosse which defended the fortress on the north side. It was made by means of a broad, deep cut into the mountain rock parallel to the wall. The purpose was to make it as difficult as possible to approach. Evidence of the work of opening the fosse on the cliff is provided by the marks left by the cutting tools in different parts of the slope. The stone that was taken from here was used to build the castle, so that the fosse also served as a quarry.

From the outside, you can see that the construction of the walls is uniform, indicating that they were built over a very short period of time. This was work done by the Templars and in some stretches it covers an earlier wall built during the time of the Moors. The Templars erected the walls using rectangular, well-hewn blocks of stone arranged in very regular rows. As the walls were intended for defensive purposes, there are very few openings in them.

At the top of the west wall, next to the central tower, you can see the remains of a latrine, an overhang built of stone from which projected a structure with an open underside. The waste drained into a dich well away from the areas frequented by the inhabitants of the castle.

The entrance is a weak point in the defence of any castle, consequently it is reinforced by a series of architectural structures intended to protect it, such as towers and a barbican. The approach road skirts the walls, following a meandering course that prevents a frontal attack and forces attacking enemies to place themselves within range of the defenders in the towers.

The barbican is a forward defence in the form of a wall that protects the entrance gate and the last stretch of the approach road. In this way, it prevents an attack on the gate launched from a distance. If the assailants reach the barbican, they are trapped between the walls and subject to attack from the towers.

The north wall is reinforced by five towers built into it but projecting forwards, giving defenders a broader field of action and ensuring no blind spots exist, thereby making it to easier to defend the approach road.

The existing walls are the result of remodelling work done in the 17th and 18th centuries to adapt the old medieval walls to more modern warfare. The construction, which combines stonework with timbering and adobe, can easily be distinguished from the Templar building work of the 13th century, visible in the Treasure Tower, which is built of regular, well-hewn blocks of stone. Even though it does not look as strong, the north wall is extremely thick, making it able to withstand the impact of cannonballs.

This tower, which has evidently been remodelled on numerous occasions, was built by the Templars on top of the old walls dating from the time of the Moors and was erected to strengthen the defences on the north side. Its forward position is crucial for controlling the entrance gate below.

The name comes from the fact that Miravet was the seat of the provincial master from the end of the 13th century and as such had custody of both the central archive of the province of Catalonia and Aragon, which contained privileges, and other important documents such as the Provincial Treasure. This consisted of the responsions, sums of money which were sent to the Holy Land to finance the Templars’ wars. They amounted to one third of the annual revenue of each commandery and the sum paid by each one was decided by the provincial chapters. In 1304 the total paid by the Catalan Templars was 1000 silver marks or 52,000 silver tornesels.

In 1307 the Miravet commandery paid a responsion of 500 masmudins or 4,500 Barcelona sous.

The existing entrance gate to the castle dates from the 17th century. Built of smaller, more irregular blocks of stone, it differs from the large ashlars used in the Templar construction that can be seen in the Treasure Tower.

The lower bailey is an enclosure that was given over to the services required for the day-to-day running of the castle. Its 12,000 m2 contained stores, stables, animal pens and yards, workshops, a water cistern and even vegetable patches and fruit trees. Most of these features left no physical evidence of their existence due to their impermanence, but we know of them thanks to descriptions given in documents.

The perimeter of this bailey is the same as that of the albacar, a walled enclosure built during the time of the Moors to protect the populace in times of danger. Built on this base, the general structure of the fortress change little over the centuries, even though it was modified in order to adapt it to advances in military technology.

The walls that protect this area reveal the different solutions found to defensive problems. To the north, the wall is reinforced by the four towers that guard the approach road; to the east, the wall has loopholes so that weapons could be fired from a safe position; and to the south, the wall is less strong but reinforces the natural defence provided by the sheer drop down to the river.

Designed as a first line of defence, the lower bailey encircles some of the upper part of the castle, the upper bailey, which constitutes a fortress in its own right.

This building, situated in the lower bailey, has been used for various purposes over the course of its history. It was constructed during the time of the Templars, as shown by the blocks of stone and the decorative band that has survived on the lower part of the wall. However, we do not know what it was used for at that time. In the 15th century it was used as stables, though it could also have housed other animals, since it is described in some documents as a cow barn. When it was used for stabling animals, the staircase was replaced by a ramp. The floor of the building was later excavated to make it level with the door, leaving the feed troughs suspended.

The building has barrel vaulting, some of which as now collapsed. According to documents, there was a second floor above used as a grain store, which has not been conserved.

Arranged on both sides of the stables is a row of feed troughs for animals. Made of stone and lime mortar, these are the originals dating from the 14th century and are remarkable, as very few such troughs have survived from this time.

At the end of the 15th century, some of the troughs were destroyed to allow an oil press to be installed. Even so, most of the troughs have survived in an excellent state of conservation thanks to the fact that they were suspended when the floor was excavated to door level in the mid-17th century.

At the back of the stables are the remains of an oil mill dating from the 15th century. To build it, the stables had to be divided and some of the troughs destroyed so that the platform on which the press stood could be erected.

Below the stables, archaeological excavations unearthed structures of Iberian and Moorish origin, providing evidence that the hill has been occupied since ancient times. The Iberian remains include walls erected on the rock, built during the time of the Roman Republic. It is impossible to trace the outline of the settlement completely, but the indications are that it climbed up the mountain. With regard to the Moorish remains, these are the bases of stone and lime mortar walls associated with fireplaces. Neither the form nor the function of these constructions can be determined, but they attest to the fact that the lower part of the castle was inhabited.

This area originally consisted of stepped terraces that followed the slope of the mountain, but in the 16th century the land was filled in to level it and a new wall was erected.

Today this terraced court is empty, but in the past it contained modest buildings used for storehouses and as animal pens and yards. Written documents also record the presence of vegetable patches and trees, including olive trees and caper bushes, to supply the residents of the castle. This area was also used as a cemetery on occasions.

With the passing of the years, the castle had to be adapted to developments in weaponry. In the 18th century, loopholes were built into the east wall. Artillerymen were able to shoot small firearms through the gap, safe from enemy missiles that were unlikely to pass through the opening. The loophole is wider on the inside than the outside, giving defenders a wider shooting angle.

_web.jpg)

The walls extend uphill beyond the lower terrace. This stretch of wall is thinner than the walls elsewhere in the fortress and dates from medieval times. As it was not subject to later modifications, we can see the original appearance of the walls as they were in the Middle Ages.

The purpose of the medieval walls was to prevent the castle from being overrun thanks to their height. Along the top are battlements, characteristic of medieval walls, that archers were able to shelter behind while defending the castle from above. a walkway, the battlement parapet, ran along the top of the walls and was narrow so that only a single person could pass.

At the bottom of the fortress are the remains of a gunpowder magazine built in the 19th century. The storage containers for the various components of gunpowder can still be seen inside. During the Carlist Wars, gunpowder made at Miravet was distributed throughout the Ebro area.

In the 17th century, work began to adapt the old medieval walls to the needs of modern warfare, in which artillery predominated. The only defence against the destructive force of cannons was to make the walls thicker, meaning that it would take assailants longer and more ammunition would be required to demolish them.

In addition to their increased thickness to withstand the impact of missiles, the new walls also had wide platforms at the top where cannons were put in place. A solid base was required to take the weight of the cannons and to cope with the recoil when they were fired.

The introduction of artillery entailed other changes. In order to move the cannons around, ramps had to be built from the courtyards to the top of the walls. In addition, openings known as embrasures had to be made in the walls to let the mouth of the cannon through.

The walls have various towers projecting from them, giving defenders a position forward of the walls and allowing them to attack the flank of enemies approaching the fortress.

Artillery was first introduced into Miravet Castle in the 17th century. In addition to reinforcing the walls, embrasures were opened into them, allowing the mouth of the cannon through while the artillerymen remained protected behind.

At this time, brick was used in the vulnerable parts of the walls, replacing stone, as bricks were better able to absorb the impact of iron cannonballs, meaning that damage was more localised and easier to repair.

The south terrace is the result of 17th-century modifications to strengthen the defences on this side. The wall is not as sturdy here, possibly because it was only intended to reinforce the effect of the natural drop.

It is believed that in the Middle Ages there was another entrance to the castle on this side, which connected it with the deserted Moorish village of Blora. Indeed, the village played an important part in the siege of Miravet by Jaume II’s army when he decreed the arrest of the Templars of the Kingdom of Aragon and the confiscation of their goods. Given the lack of results in the negotiations with the army mustered in Blora, the Miravet friars bombarded the village with two slingshots manufactured in the castle. The Templars’ idea was to force the soldiers to abandon Blora so that they could retake it and so win a way through to the Ebro, from where they could send messages and receive supplies.

The various alterations made in the 17th and 18th centuries include the construction of this bastion situated at the corner of the south and east wing of the upper bailey. The bastion stands forward of the walls, covering a larger area and eliminating blind spots for defenders.

The bastion was built by incorporating into its interior a pre-existing 14th-century tower. It is still possible to see the remains of a ramp used to transport heavy artillery from the lower to the upper bailey. Some of the loopholes for firearns still survive at the top.

From here, you can see that the upper bailey is a fortified enclosure within the castle. The only entrance is this gateway. The other openings are small and high up. The gate was protected by a ditch and guarded by the gatehouse inside the passageway.

As a result, even if enemy forces were able to occupy the first enclosure, they would not necessarily be able to take the whole castle, as the defenders could withdraw to this area.

Above the gate is a sculpted medallion that dates from the Carlist Wars in the 19th century. The medallion reads "Reynando" and carries the date of 1839. In the middle is the name "Carlos V", but this was recarved during one of the periods of Liberal occupation, since it makes reference to Carles Maria Isidre, the Carlist pretender to the throne of Spain.

The defences of the upper bailey were reinforced by a fosse, which could be crossed by means of a drawbridge. The rocks prevented the fosse from being dug deeply, but even so it made it difficult for assailants to get close to the gate.

To one side of the entrance passageway and partly excavated into the ground is a cistern built during the time of the Moors that has remained in use through to the present day.

Castles need to have access to water, especially during a siege. But Miravet Castle stands on a rock and has no springs or wells. The only way to ensure a water supply was to collect rainwater. Consequently, a cistern was cut out of the rock and a network of pipes was arranged to channel the water from the roof to here. The water tanks were sealed to prevent leakage using layers of sand and lime mortar.

This is not the only cistern in the castle, as the Templars built another in the upper bailey.

The upper bailey was the residential part of the castle. It consists of a fortified area, the only entrance to which is via a covered ramp that leads to the courtyard. The arrangement of the buildings to form four wings around a courtyard creates an enclosed space protected from the outside by the walls of the buildings and by the five defensive towers.

Some of the most important parts of the castle are located here, such as the commander's room and the church. The upper bailey was mostly built by the Templars, who designed it in keeping with the needs of the community. Their imprint still survives, even though the spaces were subsequently modified when the castle became a military barracks.

The inner court is central to the structure of the upper bailey: the Templars constructed the community's outbuildings around it, creating an enclosed space. These works were done between the close of the 12th and the 13th century in the late Romanesque style.

The courtyard we see today is larger than it was in the time of the Templars because the west-wing buildings no longer exist. Even so, evidence indicates that there was a kitchen, a mill and an oven here at various times.

The fact that the buildings of the west wing are no longer standing makes it possible for us to view the impressive defensive walls. One of the first decisions made by the Templars was to strengthen the walls by building new taller and thicker walls on top of the Moorish walls.

The old walls, which can be recognised as they are built using irregularly hewn blocks of stone and mortar, reach as high as the battlement parapet. The Templars built a new wall up against them on the outside, making the walls both thicker and higher. This new wall was made of large, rectangular, uniform blocks of stone, arranged regularly in the type of stonework termed opus quadratum.

In the centre of the inner court is a stone staircase, built in the 18th century, that leads up to the church.

To ensure maximum defensive capability in medieval times, there was no internal communication between the various floors. Consequently, the main floor was only accessible from the courtyard by means of a ladder that could be removed in times of danger, thereby isolating this floor.

It is still possible to see the identifying marks left by the stonemason on the wall of the main building, consisting of crosses, arrows and other symbols. Each of the stonemasons had his own symbol that he carved into the blocks of stone he was working on, thereby making it easier to count the pieces of stones he had delivered when it came to collecting his pay.

This space has undergone numerous changes over the centuries. It is now identified as a kitchen as records show that it was used for this purpose at one time.

In the 18th century, however, it was converted into a courtyard connecting the upper bailey with the ramp that leads up from the lower bailey. This new access made it possible to move cannons to the upper bailey and at the same time improved security because it forced enemy invaders to cross two courtyards before entering the upper bailey.

In the centre, you can still see the remains of a fireplace and an entrance cut out of the rock leading to the cistern.

At one end of the courtyard is a channel that directs rainwater from the roof to the cistern on the floor below.

The refectory was the Templar community’s dining room. The Rule insisted on readings of the holy scriptures during meals and eating in pairs to ensure austerity and poverty. The discipline of the Rule also imposed abstinence and fasting although, unlike in other monastic orders, meat could be eaten three times a week because of the requirements for good physical condition imposed by the military character of the order.

It was built during the works begun by the Templars in 1153 to adapt the old Moorish castle to the requirements of the military order. The need to expand the upper bailey prompted them to demolish the Moorish walls and to use the resulting rubble to fill in the land up to the level of the inner court. This large roof with slightly pointed barrel vaulting was built on this extended area.

The south wall, built using large blocks of stone, is also one of the defensive walls of the upper bailey. You can see how thick the wall is in the jambs of the windows.

When the castle was given over solely to military use, the refectory was turned into a dormitory for troops. The space was divided into cubicles and an intermediate floor was built. Possibly as a result of these changes, the windows lost their decorative small columns and arches.

Archaeological excavations in the refectory unearthed blocks of adobe from the old Moorish walls demolished by the Templars. These blocks, made of pressed earth and lime, were used as infill and to extend the upper bailey.

Found below ground in the refectory were five large cylindrical pillars that were part of an architectural project that was never completed. The pillars were intended to support columns that would in turn have supported a ceiling with ribbed vaulting. However, structural problems meant that the project had to be abandoned. The room was eventually given a ceiling of ribbed vaulting and the pillars were buried.

Every fortress had storehouses for oil, wine and grain to ensure that the occupants could survive a siege. The most notable feature of this space is the two silos dug into the ground.

Fortresses had various stores. This one was used for making gunpowder.

The most notable feature of this space is the three crucibles that were probably used to make gunpowder for the artillery. Each must have contained one of the three elements of gunpowder, sulphur, charcoal and saltpetre, which are combined to form an explosive mix.

In the ceiling, you can see the trapdoors used when things had to be raised to the floor above.

Even though this room is described as the cellar, it has served a number of different purposes over the course of time. As well as being used as a cellar, it has also been a storeroom, stables and even a prison at some point in its history.

The remains of an oil mill that might date back to Moorish times were found during excavations.

The gallery, which has barrel vaulting and is known as "De profundis", is the antechamber to the church and is on the first floor of the main building. It is reached from the inner court by the stone staircase, since there is no direct internal communication between the floors. Thanks to restoration work, the large windows and portal with round arches have been reinstated, as has the original red colour of the floor, the result of mixing powdered pottery with lime mortar.

The walls of the gallery still bear traces of the original decoration done during the time of the Templars. The decorative band, done on the lime roughcast, consists of black lines highlighting the vertical joins between the blocks of stone and red lines for the horizontal joins.

As well as the daily service, after Sunday mass the church was used to convene the chapter, where different matters were discussed: administration of the commandery, confession and penitence for the members of the community or the ceremony for new members joining the order.

Miravet church is incorporated into the architectural structure of the castle and cannot be identified from the outside.

Situated on the first floor, the church has a single nave and has a double-height barrel-vaulting ceiling. It has no notable decorative features, as the Templar rule demanded austerity. Even so, documents record that they had extremely valuable liturgical items.

The apse has a quarter-sphere vault and a window positioned slightly off centre because the Treasure Tower, reached from here, stands behind it. Like the gallery, the church floor consisted of a layer of lime mortar mixed with red powdered pottery.

One of the few decorative elements in the church architecture is the arch that leads into the apse. It consists of two ribbed arches that reinforce the vaulting and are themselves supported by a pillar with an embedded column.

The capitals of the embedded columns that support the triumphal arch are the only sculpted decorative elements in the church.

The walls of the church had a decorative band, like the gallery, typical of Templar constructions. You can also see some carved crosses, perhaps those of the Way of the Cross.

At the end of the church is a rose window which, when viewed from the outside, is disguised and takes the form of two windows with round arches. Its decorative features were looted in the mid-18th century when the castle was abandoned.

At the end of the room we find the spiral staircase leading to the upper terrace.

Miravet Castle, an imposing fortress surrounded by a 25 metre high wall that seems to spring from the rocks, stands on a hill dominating the Ebro river and the lands around it.

This strategic location has drawn settlements since prehistory and it has played a leading role in many conflicts.

Today we can still see part of the structures of an Andalusian fortress on top of which the Templar castle was raised immediately after the conquest of these lands by Ramon Berenguer IV. The castle was a gift to the Order of the Temple, who made it the headquarters of the Templar province of Catalonia and Aragón for what would be the period of the zenith of the power and splendour of the history of Miravet. The province became the seat of the provincial master of the Order and so was acknowledged as the most influential commandery on Catalan territory.

Although the castle was rebuilt later to adapt to the defensive requirements that arose with the coming of artillery, the appearance and the structures that have lasted down to our time are essentially the work of the Templars. And so Miravet has become one of the finest examples of Catalan military architecture of the 12th-13th centuries.

A visit to this Templar building will take us inside the monastic life of a military order governed by the strict discipline of the Cistercian Rule with a rigid hierarchy structuring an internal organisation that was ideal for a successful economic and religious administration. That also meant that it was an eye witness to the process of the suppression and extinction of the Order of the Temple.

accessibility | legal notice and privacy policy | cookies | © Departament de Cultura 2018 Agència Catalana del Patrimoni Cultural